The media is renowned for hyping things up, and yet how readily we base expectations on the skill of the camera operator.

Whoever thought of producing TV’s ‘The Repair Shop’ certainly created something special, so it’s probably natural for folk to get excited about visiting Weald Living museum, the programme’s home, just out of Chichester.

But we should not base our expectations on media hype.

Set on 40 acres, the living museum gives an insight into life across various time-frames, from Anglo -Saxon through to early twentieth century. The team have saved buildings from across Southern England, (at least five counties so far), demolitioning with care, to then rebuild at the museum.

But just getting there can be a story in itself.

Firstly, the bus driver, who’d clearly upset the cosmos. Her side mirror wouldn’t stay in place, the ticket machine was being hormonal, and a woman had tried to stop her at a non-stop by stepping onto the road and hand-signalling, despite being less than a hundred metres from a designated stop. We passengers assured her the day could only improve.

On the bus, locals shared how Jay and the team from the Repair Shop are lovely folk, despite their fame…. even using the bus, and always friendly.

Weaving our way out of Chichester, passengers came and went. The less able are so empowered by buses able to get them that wee bit too far to walk. At one stop the bus couldn’t get close to the footpath due to inconsiderate car parking, but a lady requiring her walker for balance needed to get off. Several passengers leapt up to assist.

And there’s nothing quite like the conversation of lively elderly women who no longer care about social niceties (or who’s listening.) In this case, a laughing eighty-plus was telling about when she’d been propositioned at the Bell’s bus stop. At the time she’d still been in her Sainsbury’s overalls, and was exhausted from a rough day.

In telling the story, she deprecatedly commented that there had been no spec savers in those days! Neither did she know what he intended; a quickie behind the bushes? Gales of laughter followed this idea.

As for what happened? ‘Oh, I was very polite, but pointed out my bus was due so I didn’t have time….. and he walked away.’

I wanted to hear more stories, but the friends left the bus at the next stop.

Arriving at Weald Living Museum, most visitors seem to skip the introductory phase; after all, the Repair Shop beckons. But history requires context. Why are these buildings here? Who thought of it?

Roy Armstrong saw buildings being destroyed, holus bolus, not by the bombs of World wars but during the cleanup after the first war. He first envisioned a place for rescued buildings as early as 1932, but formal discussions didn’t begin until 1965. Fortunately a site was offered two years later, and a group of volunteers enabled the museum to open in 1970 with seven buildings. There are now over fifty!

The sheer work and skill in shifting ancient structures, usually derelict, takes the visitor’s appreciation of the museum to a whole new level. The detective work required to ensure integrity and relevant historic information is also quite a feat.

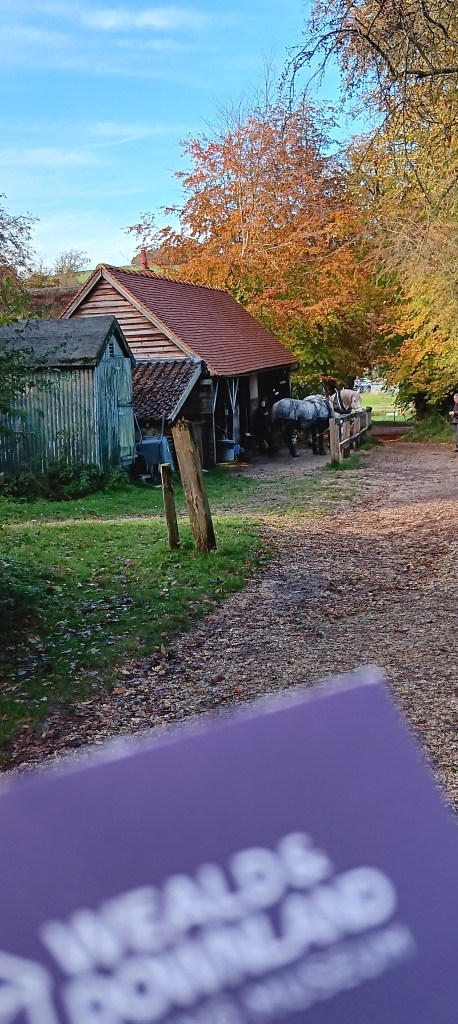

There’s a dairy from Eastwick Park Estate, Surrey, c1807:

Wandering through the various buildings, the visitor certainly gets a sense of how folk lived. The property uses Percheron horses to work the land, with historically-accurate methods. The horses earn their keep, including all their feed being provided through their own labour.

Visiting on a stunningly sunny autumnal day, with glorious colour reaching across the valley, should have been lovely, and in the landscape sense it was.

But even allowing for the forest dampness and natural life cycle of seasonal plants, there was an impression of neglect. Back in the days when folk were very dependant on what they could grow, no self-respecting kitchen garden would have allowed weeds like blackberry to run amok.

Today many historical museums and homes depend on volunteers to carry a load, and maybe Weald needs a hand? Certainly the signage needs updating, and some exhibitions need freshening. For example, the hop machinery area could do with examples of hop growing, or photo boards to show what a bine and cone looks like. Maybe a bag of dried hops so folk can smell and feel the distinctive material would enhance the visitor experience?

What they do have though includes a wim-wom, used for unrolling hop wires….

… a nidget for horse-drawn tilling between bine rows….

…and hop presses, including a 19th century version by Woodbourne of Alton.

Conversely, the well-placed seating, wide paths, and entry hall are terrific. Smells drew the passerby to the bakery, where two men were producing bread. One smell in particular took me back to my childhood, to a giant of a man by the name of Fred Conza, and his blacksmiths shop. I remember large bellows pumping air into the coal embers, making fire leap into life. Watching Mr Conza, as we kids had to call him, beat red-hot horseshoes into shape on the anvil, we were awed. Then he would drop the shoe into cold water; the resultant hiss and steam more compelling than any dragon! And of course the smell of pressing the still-warm shoe onto a horse’s hoof lingers in my memory still.

Mr Conza used to complain that my pony was so small he had to tip wee Bluey upside down to do the feet. I was never quite sure that he was joking! Nowadays blacksmithing is included on the red list of endangered trades.

Moving on from the blacksmiths shop, there’s the time-appropriately dressed man with his Flintlock black powder rifle, used for military and hunting purposes. Apparently black powder sticks and absorbs any moisture, meaning he must prick out the mechanisms after every three to four shots ; a pernickety job even with the right tool. This particular rifle was accurate to one hundred yards when aiming for an eighteen-inch square. How did they ever hit anything smaller than moose when hunting, let alone be successful in warfare?

One tool the sawmiller would appreciate: the crane for lifting logs. This is the only known working example of a hand operated timber crane from 1900, capable of shifting 5-ton logs.

In addition to the crane, there’s a Bob winch, when worked with four horses, could pull logs up to eight feet in diameter.

Inside the tenth century Anglo-Saxon cottage, note the thatch ends poking through. When the building was being worked on by the Weald volunteers, some detail was confirmed as being normal by studying water-preserved sites found in the Thames basin. A weaving frame is also on show inside this building, reflecting the inhabitants chores.

Further on, a 17th-century treadwheel rescued from Catherington, where it drew water from a 300-feet deep well, until about eighty years ago. Imagine digging down three hundred feet, by hand. Today, the sheer scale of this piece of kit is reason enough to stop by.

Another place worth stopping at is the Fittleworth mural paintings. These were done in freehand (not stencil), and were discovered underneath eighteenth century reed plaster. They may even be as early as Elizabethan.

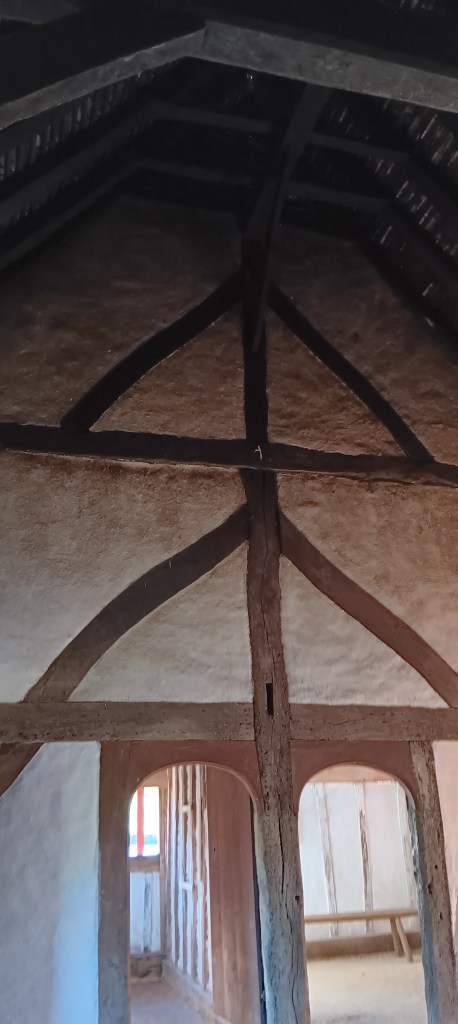

Whilst we are in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, check out these buildings:

Market hall, 1620, from Titchfield. The council chambers were upstairs, with the lock-up and marketplace below.

A three-storied 15th century shop from Horsham. The shutter at the front was lifted for opening time, and the shops had open firepits for both warmth and making goods.

A 15th-century house which was modernised in the 17th century by adding a chimney stack to replace the open fire, glass windows replacing shutters, and the area under the thatch floored in to create an upstairs room. This area previously would have been choked with fire smoke, so improvements indeed!

Early plumbing fixtures from 1797:

And still more to see:

In the area dedicated to entertainment from earlier times, versions of activities like quoits, skittles and stilts are available to try. Interestingly, it wasn’t children playing!

There is even a gypsy caravan:

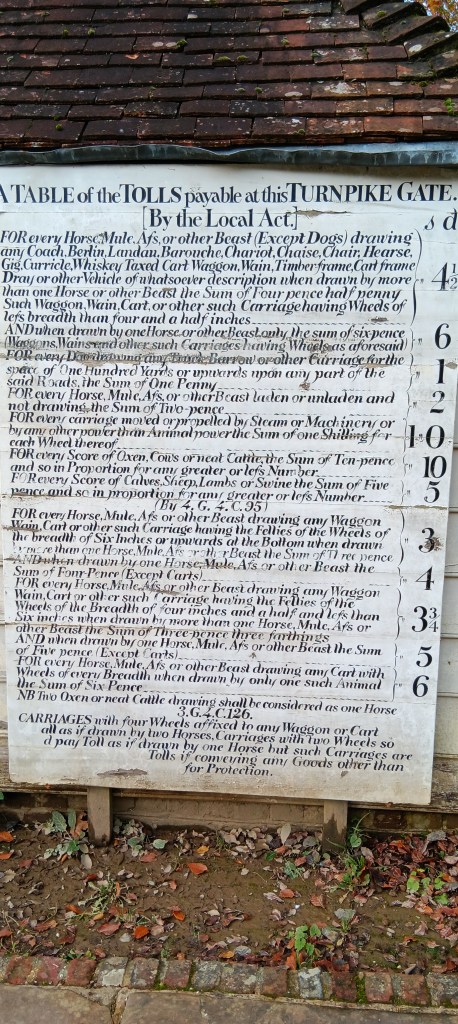

From time to time our current media broadcasts people’s dismay regarding toll roads, as we rebel against paying any extra to travel, but toll houses have been in operation for centuries.

At Weald I encountered an odd reaction, somewhat akin to shock and horror, when I asked a staff member if she’d ever visited St Fagans in Wales. She stepped back, as though I’d sworn, or worse! How sad when folk can’t see the potential in mutual support of like-minded projects.

Coming back to The Repair Shop, it’s so much smaller in real life. Somehow I’d got the impression it was right by the lake, but no, the lake is beautifully placed by the cafe and entrance.

The Repair Shop building is an ex-threshing barn. Above the door are the original boxes for encouraging owls to nest, as a form of biological control of mice and rats.

Before you visit, put aside your TV-induced preconceptions. Weald is certainly worth a visit, educationally, historically, and machinery-wise. Families and other folk can enjoy lovely picnic areas, excellant pathways, and masses to see.

As you wander around, remember that annual memberships help keep this treasure alive, so do consider it. And back at home, find that something (or someone) near you who could do with a bit of your time, if you haven’t already.

Loved the pictures, I can imagine you having a lovely day poking into all the corners!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really did!

LikeLike