In 1565, fifteen-year-old Helena Snachenberg from Sweden became Maid of Honour to Queen Elizabeth the First. Helena must have been quite a girl, as she married a Marquess, and then a Sir Thomas. She died aged 86, leaving ninety-eight descendants! She and her Sir lie together in Salisbury cathedral.

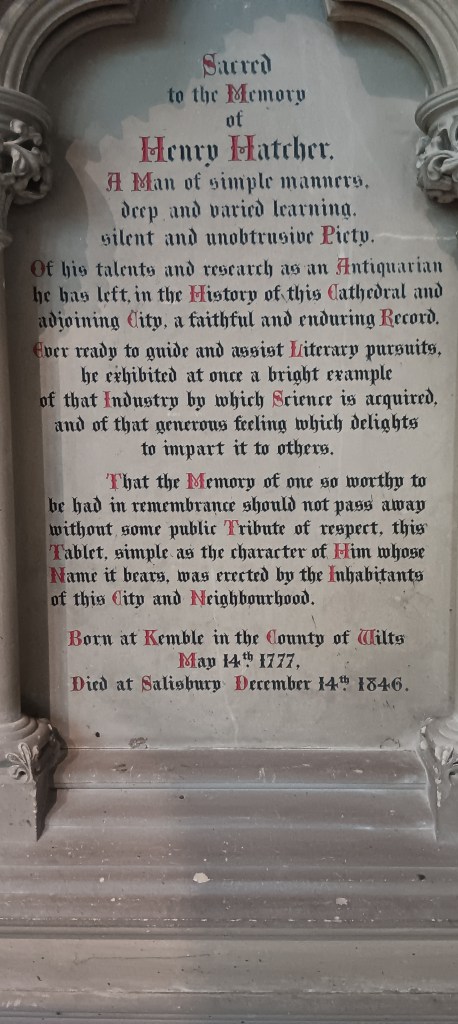

The cathedral has surprising memorials. A plumber who sorted out the drains is remembered, as is an antiquarian.

And a simple memorial:

A stained glass window memorialises the glider pilots who died in wartime between 1942 and 1945. Their regiment was the forerunner to the UK’s Army Air Corps.

Another young man remembered from war time, for a special reason:

The cathedral itself has some unusual features. Firstly, the foundations are only four feet deep. That such a vast structure could stand for so long on short legs is surprising, but trouble is in the air; look up and see the curvature developing in the black columns.

The short foundations are due to the water table and gravel underlay. Cathedral personnel lift an eight-inch square block from the middle of the cathedral floor to reveal water just eighteen inches below. Like so much of Salisbury, the water table is very high, and has been known to bubble up to cover the floor, after excess rainfall. The archer responsible for the siting of the cathedral should have been more careful.

Legend tells us the area had a church structure, built 1075, known as the ‘Old serum,’ high on a hill, but the priests were tired of the wind, the citizens were reluctant to climb with their loads, and water was problematic. A new cathedral was proposed, but no agreement of a site came forth. The area’s best archer was engaged, with the idea he should fire an arrow from the hilltop, and wherever it landed would be the new site. Great idea. But they had not counted on a deer. The arrow pierced the deer’s rump. Naturally he took exception to this, and ran. Where he finally fell, two miles from the archer, became the new site.

Construction required not only expensive materials (marble was barged in) but also years of work by skilled craftsmen. Laborers were paid 1 & 1/2 pennies per day, at a time when one penny could buy 2kg’s of wheat, or a bottle of wine. However, all was not lost; if you died on the job, as many did, you were buried in a graveyard adjacent to the cathedral, regardless of your work position, so laborers lie beside masons in the cathedral’s only graveyard.

The cathedral project took thirty-eight years to complete, starting in 1220.

Like all great cathedrals, it has a grassed inner area to one side, graced by arch-lined walkways for contemplations and walking.

In 1225 the deep blue (almost black) windows of the Trinity chapel section were consecrated. Early morning sunrise best reveals the wonder of the coloring and creativity.

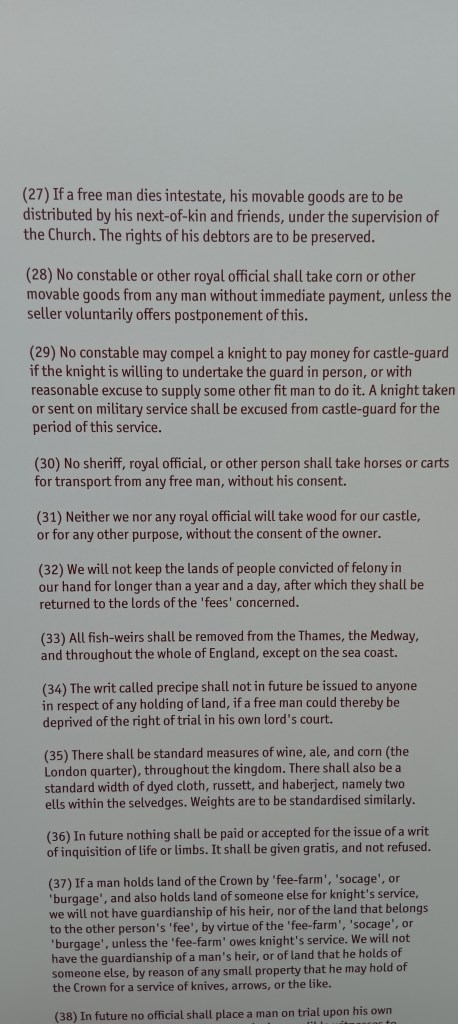

One of the great ironies of English cathedrals lies in Salisbury Cathedral: the Magna Carta. King John was essentially forced to agree to signing this document, brought about by a daring group determined to stop the King’s behaviour. Shades of Robin Hood maybe, who is purported to have been from King John’s time. The Magna Carta granted the common people rights to their belongings, including stock. It is seen as the founding document of modern United Kingdom. Certainly it’s impact was immense.

And the irony? King John’s tyranny brought about the need for the Magna Carta, and yet he lies in state in Worcester Cathedral for all to admire. How mad.

The writing of the Magna Carta was completed using quills, and ink made from crushed oak galls, water, iron salt, and dried tree sap. The quills came from a birds left wing, for right-handed scribes, and right for left-handed.

Going back to Robin Hood for a moment, one of my ancestors was a Sherriff of Nottingham, but fortunately a couple of centuries before the notorious sheriff who stole anything he fancied and was as evil as all villains should be. My sheriff was simply an earlier version of today’s Mayor’s, and is thus lost to the depths of history.

Someone who was definitely worthy of remembering is Margaret of Wessex who married King Malcolm the 3rd of Scotland. She was renown for her acts of piety and charity. The chapel of St Margaret (within the cathedral) is now a focus of prayer for the Mothers Union, which is in keeping with the cathedral’s strong history of community events in and around the building. During the Covid pandemic the cathedral was a vaccination centre, responsible for injecting protection to thousands.

Salisbury continues to act with the times, partnering with Sudan and South Sudan churches to provide support.

In the days before clocks as we know them, priests lived their lives by the bells. Time was differant then, or rather, the times we use were. Noon was at approximately 3pm ie the ninth bell of the day. The first bell was about 6am. To get the times right, from 1386 a cloche (or glock) was used which did not ‘tell’ the time, and had no face. The example in Salisbury cathedral is the oldest working clock in the world. It has no nuts and bolts, using metal pegs instead. Minutes didn’t exist back then. Imagine a time when no-one could say ‘in a minute’ or ‘just a second.’ Each area of the UK had their own timezone, which was finally standardised in 1886 for the convenience of the trains.

Be at the cathedral at 11am to hear the explanation, and see this marvelous device in action.

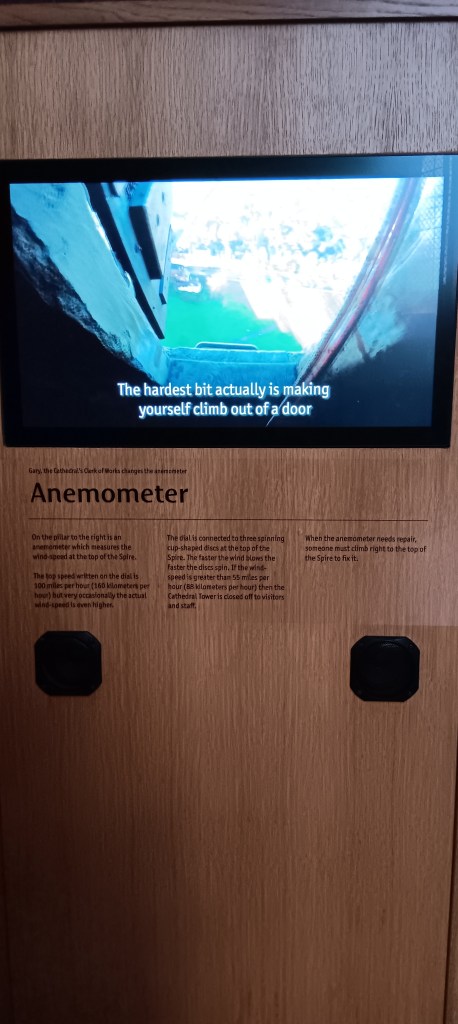

While you are there, note the anemometer situated 404 feet up on top of the spire, and just be glad it’s not your job to maintain it; watching the video is enough! The first photo is the view from the top…

And see if you can figure out why the lectern needed a ‘hat’ or ‘lid.’

In a side room rest the priests chests for the safekeeping of documents and money. Between 1250 and 1500 these chests needed seven locks to be opened for access, but each key was held by a differant priest, and no-one was allowed to know all the keepers identities. This meant everyone had to agree before a chest could be opened. You wouldn’t want to be the one who lost your key!

Down in the town of Salisbury is the last surviving example of the cities four ‘crosses.’ These structures marked the tradional centre’s for markets. The Linen, Cheese and Bernewell crosses may all be gone, but the Poultry cross, built 1335, stands proudly in the city, appropriately the favorite haunt of countless pigeons.

Pigeon offerings are much easier to find in the central city than sandwiches and cake not pre-wrapped in single-use plastic. Eventually I settled for a pastries and cake cafe, which doesn’t do sandwiches or wraps, but also has no sign of plastic. A four-year-old let me know the cafe does ‘Amazing’ icecream! It’s a crime that I wasn’t in the market for such treasure. The ‘orange pie’ looked like cake, with no pastry in sight. A slice of glazed orange adorned each portion, and the whole thing swam in about five mls of orange juice mixed with glaze. I wasn’t in the mood to try that either.

Outside, the cafe opened onto a square. The trees appear to be surrounded by soft bark, but sadly it’s a matting which allows no natural composting or root eco-systems to thrive.

But back to Salisbury Cathedral, where the most modern christening font encapsulates the old and the new, whilst acknowledging the very basis upon which it sits. All power to them for embracing their challenges.

Salisbury cathedral: wonderful!